The Climate Commission has released for consultation its draft report setting out what it thinks needs to happen for the country to be carbon neutral by 2050. Its vision statement sets out how it wishes New Zealand to develop and includes this passage:

It is an Aotearoa where cities and towns are created around people and supported by low emissions transport that is accessible to everyone equally. Where strong local businesses produce low emissions, high-value products that are in demand locally and globally. Where employers are successful and can support themselves and their employees in the transition to climate-resilience. Where everyone lives in warm, healthy, low emitting homes. Where urban form encourages cycling and walking, alongside efficient, affordable and interconnected public transport networks.

It points out that Transport contributes over a third of New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions. It’s recommendations about transport include these:

An integrated national transport network should be developed to reduce travel by private car. There needs to be much more walking, cycling and use of public and shared transport …

Our analysis shows that reducing transport emissions is crucial to meeting our emissions budgets and reaching net zero by 2050 – this will have an immediate and lasting impact.

This means changing the way we travel and move goods. New Zealanders should be able to walk and cycle more. Freight will need to come off the road and onto rail and shipping.

To lower emissions we will need to change the way we plan and build our cities to make it faster and easier to get around. Having an integrated public and shared transport system both locally and across Aotearoa will encourage a shift in the way we live and travel.

Its goals are ambitious. It proposes that the importation of petrol driven cars stops at some stage between 2030 and 2035. It assumes that the average household travel distance per person can be reduced by around 7% by 2030 and believes that the share of this distance travelled by walking, cycling and public transport can be increased by 25%, 95% and 120% respectively by 2030.

The question arises. What shape is Auckland in to handle a significant increase in walking and a doubling of cycling and public transport trips in the next decade?

The answer appears to be not as well as could be hoped for.

The Herald’s Simon Wilson recently wrote about the botched up Tamaki Drive cycleway.

He said this:

But the city cries out for more cycleways and progress building them is painfully slow. Tāmaki Drive should not be allowed to slow up what little else is being done. Fix it when it comes up on the maintenance schedule.

What AT needs to fix now is its cycling project delivery unit.

That’s no small job. It has to rethink which jobs get done, and how, and it has to think exponentially bigger. An entirely new strategy is required.

Wilson reviewed a recent Council meeting where a number of different groups urged Council to take more action. The meeting even included the threat of legal action.

… Jenny Cooper from Lawyers for Climate Action reminded the councillors they have legal obligations to meet emissions targets. Her group was “very prepared to test this in court”.

That did it. Cr Jo Bartley, who represents poorer suburbs like Otāhuhu, was furious. “We get so much hate about bike lanes,” she said. “We don’t need threats from you as well. To hear you guys say you’re going to sue us, it just sucks. If there’s any chance you could bypass us and just sue the haters, that would be great.”

“It does suck,” said [All Aboard’s Paul] Winton, not backing down. “And it’s the burden of leadership. We thank you, the people in this room. But there are about 14 per cent of people who don’t believe climate change is a thing. They’re the haters, but they are the loudest voices. The science says, ignore them.”

In an earlier column about how Auckland could reduce its transport emissions by 70% Wilson said this:

Cycling costs almost nothing compared to trains and buses, despite the occasional complainant thinking otherwise, but Auckland still doesn’t have much cycling infrastructure and progress is painfully slow.

Could cycling become as popular here as it is in Copenhagen? They have 1.3 million people and a third of trips in the city area on a bike. Being like the Danish capital would save 375 kt CO2-e of emissions.

This is the second surprise: cycling could have a bigger impact on emissions than public transport.

To achieve it would require enormous new commitments from politicians and transport officials: much bigger cycling networks, more arterial routes, more dedicated lanes in and around town centres and schools and substantial subsidies for e-bikes.

But Auckland Transport isn’t interested. It’s spending only $600 million on cycling over 10 years and there’s almost no sign of any official enthusiasm anywhere to step that up.

He also advocated for reducing car trips by 50%. Good walkways can do this. But they have to be built.

The Waitakere Ranges Local Board has been keen to do what we can to make our city more sustainable. We have declared a climate change emergency. And we have completed our Greenways Plan, a blueprint of a walkways and cycleways network that will make the area more walkable and bikeable.

We used to have a Capital Fund allocated by Auckland Transport that could be used for projects like these. In the past the fund has been used for projects such as the Oratia Cycleway and the Henderson Valley Walkway. In the past few years we have also built the Little Muddy Creek walkway and the Rimutaka Road walkway. We really do want to make the area more walkable and improve accessibility for those not wanting to use a car.

We were planning on using a significant amount to develop a town square in Glen Eden. With the opening of the City Rail Link the area will become really popular. The signs are already there with three apartment towers having just been completed or currently under construction and with many more to come.

But with a delay in funding for the project I wanted us to complete as much of the greenways plan as we could in the meantime.

In May 2020 we were advised that we had $3,524,792 available to spend on local capital projects. Following the Covid emergency budget it was something of a shock to discover that the money had apparently disappeared.

To achieve anything in local government fine words are not enough. There has to be budget and political consensus to spend the money and to resist the temptation to fiddle with it.

And this is where the politics gets real. Passing climate change emergency resolutions is a start. Allocating budget for construction is what has to happen.

I hope that Auckland Council and Auckland Transport can reinstate the funding. I am happy to get the Board’s pledge to spend the money on our greenways plan.

My very rough back of the envelope estimate is that it would cost $50 million and take ten years to complete, just in time for the Climate Change’s purposes. The annual cost would be $5 million. We used to be allocated $2 million a year for capital projects.

If the same grant was made to each local board the annual budget would be $105 million a year. On top of the regional budget this would nearly treble the spend on cycleways each year.

How does the city fund these? Start cancelling road projects. Cars will become a less and less important feature of our city, unless we have totally failed and have blown our aspirations to contribute our part to survival of the planet’s ecology.

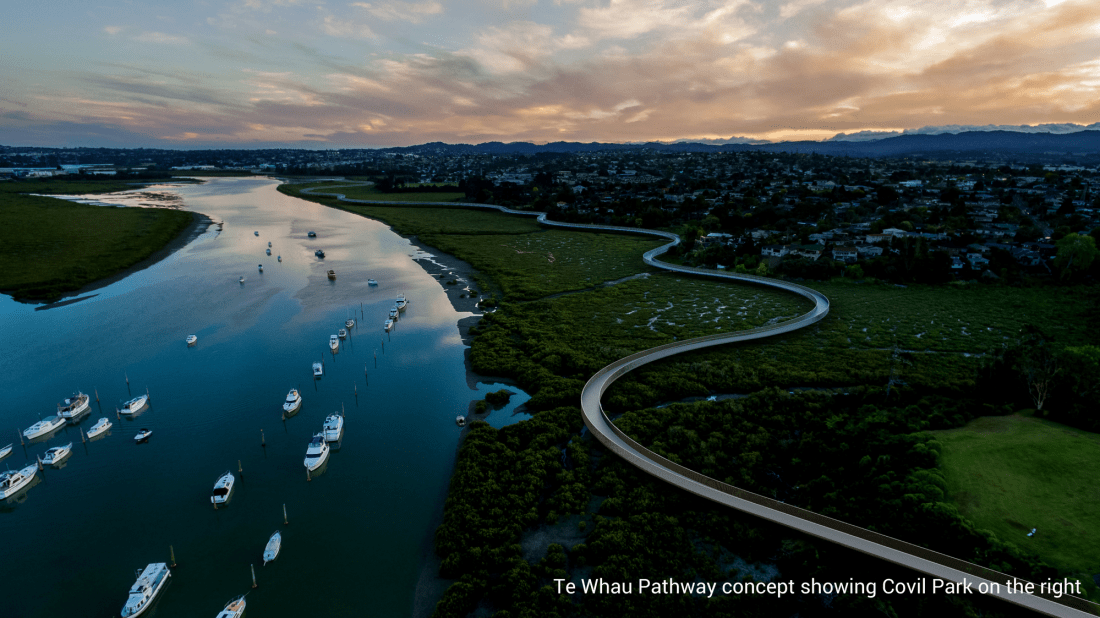

Regional projects will continue to be vital to provide the backbone to the local connections. One of the most significant currently is the Whau Coastal Walkway, a project initiated privately by a trust I am a member of. Letting local boards also plan their greenways and then engage with Auckland Transport to get the regional projects built will accelerate the greening of our city.

I was first elected to public office in 2001. Back then I thought that climate change was a crisis and we had to take action. Locally and centrally a lot has been achieved but not nearly enough and we are now in a race against time. We are now at the point of no return and if we want to prevent the worst excesses of it happening we have to take unprecedented and radical action. Now.

Leave a Reply